Dr. Mitch Broser

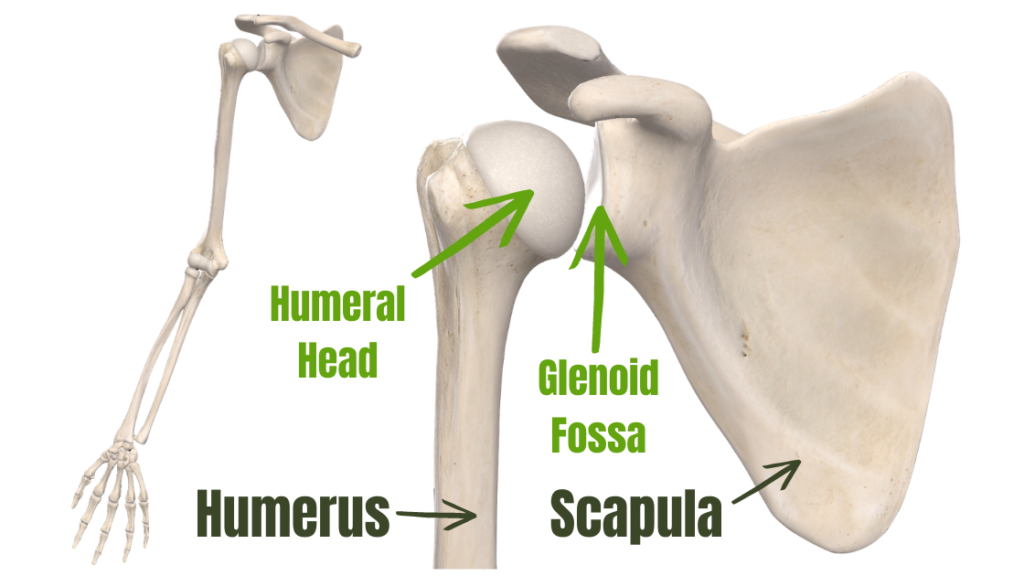

The rotator cuff is a confluence of 4 muscles: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis and teres minor. Despite being called the “rotator” cuff, these muscles aren’t major rotators. Their primary function is to keep the head of the humerus depressed and centered into the glenoid fossa. This isn’t to stabilize or limit motion – its to allow efficient motion in all directions. The tendons of these four muscles attach into the shoulder joint capsule, engulfing the head of the humerus and holding it within the glenoid fossa.

How do you tear your rotator cuff?

There are 2 mechanisms of rotator cuff tears. First, it can be from a one-time acute traumatic incident such as a hard blunt-force trauma or shoulder dislocation. Second, it can be degenerative in nature, where repetitive microtrauma (ie. force loads) leads to partial-thickness tears that can gradually progress into full thickness tears. Degenerative tears are much more prevalent than acute traumatic tears.

Partly due to the poor blood supply, the rotator cuff’s tendinous insertions have poor healing capacity as tears normally worsen with age. There is a 50% chance of rotator cuff tear after 60 years old, with tear rates increasing 13% to 51% from 50 to 80 years old. The degenerative process also leads to muscle atrophy (decrease in mass of the muscle) and weakness. The degradation of tendon tissue quality along with the imbalance of muscle function between all of the rotator cuff muscles leads to a high risk of tear progression. Even when rotator cuff tears are acute, they often have pre-existing underlying poor tendon and/or joint capsule tissues that make them more vulnerable to overloading and injury.

Where does the tear happen?

Rotator cuff tears occur more commonly near or at the ends of the rotator cuff tendons as they attach into the shoulder joint capsule and humeral head. Keep in mind that the tendons are 3 dimensional – almost tubular. Tears can happen around the perimeter of the tissue or deeper within it. Intrasubstance tears (tears from inside the tendon) are twice as common as tears from the outside. Tears that happen from the outside can occur at the bursal surface (top part) or articular surface (under surface) of the tendon. The stress-failure point of tendon on the articular side is half of that on the bursal side, making articular-side tears more common.

Partial thickness tears include tears that don’t go all the way through the tendon. These tears range in severity based on tear size, location, symptoms and shoulder functionality. About 10% of partial thickness tears heal, 10% become smaller, 53% propagate (expand and spread) and 28% become full-thickness tears. A full thickness tear refers to a tear which goes all the way through a rotator cuff tendon. These tears are usually much larger, have a much poorer prognosis, and depending on where the tear occurs, are more detrimental to shoulder function. Full-thickness tears don’t heal spontaneously and a majority (36-50%) progress. The onset of pain or worsening pain, with or without accompanying weakness in active arm elevation is usually a sign of increasing cuff tear size.

What do we do with rotator cuff tears?

There are many factors which influence management decisions and prognosis. Typically, for those with manageable or no symptoms and can elevate their arm enough for their activities of daily living, surgery isn’t advised. However, those who experience significant pain and can’t elevate their arm enough for their activities of daily living are most often surgical candidates. Although there is a good prognosis for those with smaller, newer partial-thickness tears, those with more significant tears or are older in age see a diminishing prognosis. Recovery from surgery can also be long and difficult since minimal exercise is advised in the first several months, depending on patient demographics and health factors. For the non-surgical route, activity modification, analgesics, steroid injection and physical therapy is recommended. Of course, I will elaborate more on the physical therapy component of care.

Therapy and Training

Traditionally, rotator cuff strength training has emphasized rotation-based exercises, such as shoulder internal and external rotation with a resistance band. However, as I mentioned at the beginning, the primary function of the rotator cuff is not rotations, its to compress and centralize the shoulder joint! The rehabilitation and training should be geared toward improving the primary function and improve the tissue quality of the cuff and shoulder joint capsule. Concentric internal and external rotation strengthening with a resistance-band is not specific enough to isolate the tissues that need it most (ie. at the location of the tear to improve tissue quality and integrity). These types of exercises cyclically load tissues and produce a greater inflammatory response. Compared to concentric strengthening, Isometric strengthening (sustained, without movement) illicit less of an inflammatory response, have a greater analgesic effect and provide a potent stimulus to improve tissue quality, compared to concentric muscular contractions.

Training and treatment inputs should specifically target the pathological tissue in order to restore tissue viability. Rotator cuff tears occur most often at the very distal end of the tendon, or within the joint capsule where they attach. The most specific way to load and train the deepest tissue of the shoulder joint is through rotational-based exercises. The goal of the exercise is to increase tissue viability and promote tissue-to-bone healing. In symptomatic or post-surgical rotator cuff tears the amount of loading should be kept to a tolerable level. Starting with low intensity muscular contractions, we can progressively train tissues with greater force to help guide tissue healing and optimize tissue integrity.

References:

- Pandey V., Willems WJ. Review article – rotator cuff tear: a detailed update. Asia-Pacific journal of sports medicine, arthroscopy, rehabilitation and technology 2. 1-14. 2015